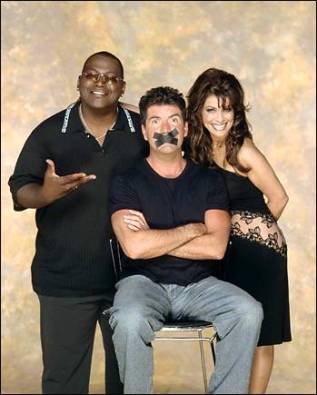

On the American Idol finale, Judges Randy Jackson and Simon Cowell reminded us repeatedly, lest we forget, that American Idol is a singing competition first and foremost. Blake Lewis and Jordin Sparks are the two finalists this year, suggesting that they are the two best singers (under the age of 29) in the country. Makes sense, right? Not so fast. Beneath the surface, myriad situational factors conspire to suggest that for all American Idol is — pop culture phenomenon, money-making machine, and career maker for Simon Cowell — it is not a meritocratic selection process that reliably delivers up the best singer each year.

Not so fast. Beneath the surface, myriad situational factors conspire to suggest that for all American Idol is — pop culture phenomenon, money-making machine, and career maker for Simon Cowell — it is not a meritocratic selection process that reliably delivers up the best singer each year.

First, think of the auditions: Isn’t it odd that we see thousands of people waiting to audition, even though there are only a few days of auditions in each city? Conservatively estimating, about ten thousand people auditioning for thirty seconds each means about 5,000 minutes — almost a week’s worth of auditions, even if the judges worked for twelve hours a day. Are Randy, Paula, and Simon burning the midnight oil auditioning hopefuls? Of course not: Idol contestants first audition — off-camera — in front of panels of the show’s staff. And because of the overwhelming number of aspirants, many cities ban contestants from camping out overnight. Thus, because of the high demand, even if you show up at the appointed place at the appointed time, “there’s still no guarantee you’ll actually get to audition.” How do we know the next Fantasia or Taylor wasn’t eliminated merely by virtue of timing?

Even if you were a contestant who got to audition, you would realize that you’re called, three or four at a time, to audition for about fifteen seconds in front of a panel of three of the show’s producers. Again, notice the invisible situational influence: if the others you’re teamed up negatively color your performance, even the most talented singer could be sent packing, without so much as an, “Atrocious!” from Simon.

Those who pass the first audition in front of the show’s producers go on to a second audition in front of the show’s executive producers, and about 100 to 200 of these (twice-successful) contestants go on to round three, auditioning before the show’s trio of celebrity judges — that is, what we in the TV audience think of as the “first” audition. But as everyone knows, despite Randy’s and Simon’s insistence, Idol is not just a singing competition; as Simon has explained elsewhere, the point of the international Idol franchise was to make money for the various shows’ parent corporation. So when the first 98% or 99% of contestants are eliminated by the show’s producers, they are looking, not just for the best singer, but for the most marketable contestant so that the company can maximize its profits in the marketplace. Again, this situational element goes largely unmentioned. After all, it is far sexier to say that Carrie or Kelly is the best singer in

America than it is to say that she was the best moneymaker the producers found.

Also notice that the audition process takes several days. Although there are many who would love to take the time off from school or work (assuming they are in school or at jobs) to audition, there are many who simply cannot afford to do so. The “neutral” audition process thus serves to exclude all of those who — no matter how talented — cannot manage to sacrifice several days’ worth of wages or classes for their shot at stardom. Idol, then, involves a self-selection process, through which only those with the financial, social, and emotional capital to invest in such a long audition process even bother to show up.

On other websites, several people take issue with the way their auditions were portrayed. For example, contestants allege that the show’s producers spliced audition tapes or coached contestants to say or do embarrassing things for the benefit of the show’s ratings. But even if these stories of deliberate manipulation are false, it is clear that the audition process involves lots of more subtle — but equally important — situational manipulation.

For example, at the audition in front of the celebrity judges, the market’s situational factors pervade the process. How many times have we seen a judge tell a contest that she not skinny enough, or attractive enough, or charming enough, to make it as a pop star? If the show is a singing competition first and foremost, why did Simon tell the Maynard Triplets in Season Four that they were overweight and thus wouldn’t be able to move on to Hollywood? The reply might be that Simon was just being honest; he was informing the triplet (and others) of what the market would bear. But for all of its power, surely Idol has the power to affect the situation; if Idol’s star judges say a girl can sing, she will gain at least some publicity and success. Indeed, the year before Simon dismissed the triplets, the Idol, Reuben Studdard, was no model of physical fitness himself. In rejecting the triplets, Simon reinforced gender stereotypes and caved to market pressures in a show that — lest we forget! — is all about one’s singing talent.

But what about the vote? After all, in a variety of contexts, from governmental elections to contests for corporate control, the vote is held up as an almost-sacred form of legitimacy: if “the people” (or the shareholders, or the Idol viewers) chose it, it must be good, right? Well, sort of. First, the voting on Idol does not begin until the top 24 contestants are chosen — that is, until after the producers and executive producers panels’ have cut about 99% of the contestants at the first two auditions, and after Randy, Paula, and Simon have cut the remaining crop (usually between 150 and 200) down to 24. In other words, the “choice” that viewers have is remarkably limited: about 100,000 people auditioned for season six, and viewers could only choose among twenty-four. It does not take much of a leap of the imagination to think that those twenty-four were chosen for qualities that had at least something to do with factors other than musical ability.

Still, at least we can choose among the final twenty-four, right? Even if the field was narrowed for viewers, perhaps the show’s judges and producers served a useful function; after all, even if each Idol voter wanted to pick the best contestant, surely she would not have the time or patience to wade through 100,000 hopefuls.

But after the top 24 are selected, the judges’ roles become interesting. The judges’ views theoretically carry no more weight than yours or mine — all they can do is vote like the rest of us — so why do they exist at all? Perhaps the judges make for good ratings, but perhaps there is more to it. Sanjaya, this season’s lovable loser, managed to make it to the final seven. He was voted through week after week — until Simon’s comment on April 17 that he had had a good run and it was probably his time to go. It was not clear that Sanjaya’s performance was much worse on April 17 than it was, say, on April 10. Why was he voted off?

But after the top 24 are selected, the judges’ roles become interesting. The judges’ views theoretically carry no more weight than yours or mine — all they can do is vote like the rest of us — so why do they exist at all? Perhaps the judges make for good ratings, but perhaps there is more to it. Sanjaya, this season’s lovable loser, managed to make it to the final seven. He was voted through week after week — until Simon’s comment on April 17 that he had had a good run and it was probably his time to go. It was not clear that Sanjaya’s performance was much worse on April 17 than it was, say, on April 10. Why was he voted off?

Instead, it is probably the case that Simon’s comment served as a framing effect. Even though there was probably little changes in the “merit” of Sanjaya’s singing or his “disposition” between weeks, even relative to other contestants, Simon’s comments on the 17th altered the voters’ situation, such that Sanjaya’s storied run came to an end the next night. In the same vein, the judges comments from week to week exert a similar situational influence on the voters, focusing them on certain singers, framing their perception of the singers’ qualities, or suggesting that certain contestants were (or were not) safe, thus leading people to believe their votes would be irrelevant.

The list of situational factors goes on: some contestants are voted off because they couldn’t pull it out on Country

Music Night, or ‘80s Night, or Bon Jovi Night — even though we all know that few if any pop stars are that versatile. The finale’s “songwiter’s choice” piece was “neutral” in that it was the song performed by both finalists, but it clearly served to showcase Jordin’s voice more than Blake’s style. The judges and producers thus exert significant influence, direct and indirect, conscious and subconscious, on the voters’ “choices” — even though these votes are supposed to be paramount.

In any event, one thing is undoubtedly clear: Blake Lewis and Jordin Sparks are tremendously talented performers, and both will go on to have great careers. However, it is equally true that, for all it is, American Idol is — as markets generally are — as much about packaging, behind-the-scenes manipulation, and situation. Jordin might be the next American Idol, but she, Blake, and the rest of us are all situational characters.