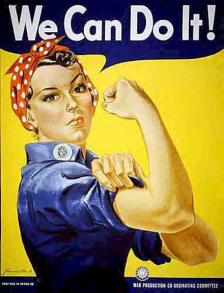

Women’s Situational Bind

Posted by The Situationist Staff on December 1, 2007

Last month, Lisa Belkin wrote a terrific summary (in the New York Times) of recent findings regarding the role of stereotypes in creating double binds, glass ceilings and other situational impediments to their success in upper echelons of the workforce. The name of her piece was “The Feminine Critique,” portions of which we excerpt below.

Last month, Lisa Belkin wrote a terrific summary (in the New York Times) of recent findings regarding the role of stereotypes in creating double binds, glass ceilings and other situational impediments to their success in upper echelons of the workforce. The name of her piece was “The Feminine Critique,” portions of which we excerpt below.

* * *

DON’T get angry. But do take charge. Be nice. But not too nice. Speak up. But don’t seem like you talk too much. Never, ever dress sexy. Make sure to inspire your colleagues — unless you work in Norway, in which case, focus on delegating instead.

Writing about life and work means receiving a steady stream of research on how women in the workplace are viewed differently from men. These are academic and professional studies, . . . and each time I read one I feel deflated. . . .

“It’s enough to make you dizzy,” said Ilene H. Lang, the president of Catalyst, an organization that studies women in the workplace. “. . . [W]e still don’t have a simple straightforward answer as to why there just aren’t enough women in positions of leadership.”

Catalyst’s research is often an exploration of why, 30 years after women entered the work force in large numbers, the default mental image of a leader is still male. Most recent is the report titled “Damned if You Do, Doomed if You Don’t,” which surveyed 1,231 senior executives from the United States and Europe. It found that women who act in ways that are consistent with gender stereotypes — defined as focusing “on work relationships” and expressing “concern for other people’s perspectives” — are considered less competent. But if they act in ways that are seen as more “male” — like “act assertively, focus on work task, display ambition” — they are seen as “too tough” and “unfeminine.”

Women can’t win.

In 2006, Catalyst looked at stereotypes across cultures . . . and found that while the view of an ideal leader varied from place to place . . . whatever was most valued, women were seen as lacking it.

Respondents in the United States and England, for instance, listed “inspiring others” as a most important leadership quality, and then rated women as less adept at this than men. In Nordic countries, women were seen as perfectly inspirational, but it was “delegating” that was of higher value there, and women were not seen as good delegators.

* * *

While some researchers . . . tend to paint the sweeping global picture — women don’t advance as much as men because they don’t act like men — other researchers narrow their focus.

Victoria Brescoll, a researcher at Yale, made headlines this August with her findings that while men gain stature and clout by expressing anger, women who express it are seen as being out of control, and lose stature. Study participants were shown videos of a job interview, after which they were asked to rate the applicant and choose their salary. The videos were identical but for two variables — in some the applicants were male and others female, and the applicant expressed either anger or sadness about having lost an account after a colleague arrived late to an important meeting.

while men gain stature and clout by expressing anger, women who express it are seen as being out of control, and lose stature. Study participants were shown videos of a job interview, after which they were asked to rate the applicant and choose their salary. The videos were identical but for two variables — in some the applicants were male and others female, and the applicant expressed either anger or sadness about having lost an account after a colleague arrived late to an important meeting.

The participants were most impressed with the angry man, followed by the sad woman, then the sad man, and finally, at the bottom of the list, the angry woman. The average salary assigned to the angry man was nearly $38,000 while the angry woman received an average of only $23,000.

* * *

Also this summer, Linda C. Babcock, an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon University, looked at gender and salary in a novel way. She recruited volunteers to play Boggle and told them beforehand that they would receive $2 to $10 for their time. When it came time for payment, each participant was given $3 and asked if that was enough.

Men asked for more money at eight times the rate of women. . . .

There are practical nuggets of advice in all this data. . . . “Some of what we are learning is directly helpful, and tells women that they are acting in ways they might not even be aware of, and that is harming them and they can change,” said Peter Glick, a psychology professor at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wis.

He is the author of one such study, in which he showed respondents a video of a woman wearing a sexy low-cut blouse with a tight skirt or a skirt and blouse that were conservatively cut. The woman recited the same lines in both, and the viewer was either told she was a secretary or an executive. Being more provocatively dressed had no effect on the perceived competence of the secretary, but it lowered the perceived competence of the executive dramatically. (Sexy men don’t have that disconnect, Professor Glick said. While they might lose respect for wearing tight pants and unbuttoned shirts to the office, the attributes considered most sexy in men — power, status, salary — are in keeping with an executive image at work.)

wearing a sexy low-cut blouse with a tight skirt or a skirt and blouse that were conservatively cut. The woman recited the same lines in both, and the viewer was either told she was a secretary or an executive. Being more provocatively dressed had no effect on the perceived competence of the secretary, but it lowered the perceived competence of the executive dramatically. (Sexy men don’t have that disconnect, Professor Glick said. While they might lose respect for wearing tight pants and unbuttoned shirts to the office, the attributes considered most sexy in men — power, status, salary — are in keeping with an executive image at work.)

But Professor Glick also concedes that much of this data — like his 2000 study showing that women were penalized more than men when not perceived as being nice or having social skills — gives women absolutely no way to “fight back.” “Most of what we learn shows that the problem is with the perception, not with the woman,” he said, “and that it is not the problem of an individual, it’s a problem of a corporation.”

* * *

To read all of Lisa Belkin’s excellent piece, click here.

Several Situationist contributors are doing pathbreaking work related to the topics discussed in this post, including Susan Fiske (e.g., Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social perception: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Science, 11, 77-83) and Geoffrey Cohen (e.g.,. Uhlmann, E., & Cohen, G. L. (2005). Constructed criteria: Redefining merit to justify discrimination. Psychological Science, 16, 474-480). For related Situationist posts, see “Being Smart about ‘Dumb Blonde’ Jokes,” “Gender-Imbalanced Situation of Math, Science, and Engineering,” “Sex Differences in Math and Science,” “You Shouldn’t Stereotype Stereotypes,” “Women’s Situaiton in Economics,” and “Your Group is Bad at Math.”

Rate this:

Related

This entry was posted on December 1, 2007 at 2:47 am and is filed under Implicit Associations, Life, Social Psychology. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Susan Fiske — on Teaching Situationism « The Situationist said

[…] Women’s Situational Bind […]