Deep Capture – Part VI

Posted by J on December 21, 2007

This is the sixth of a multi-part series on what Situationist Contributor David Yosifon and I call “deep capture.” The most basic prediction of the “deep capture” hypothesis is that there will be a competition over the situation (including the way we think) to influence the behavior of individuals and institutions and that those individuals, groups, entities, or institutions that are most powerful will win that competition.

capture.” The most basic prediction of the “deep capture” hypothesis is that there will be a competition over the situation (including the way we think) to influence the behavior of individuals and institutions and that those individuals, groups, entities, or institutions that are most powerful will win that competition.

I review the previous posts in this series at the bottom of this post, which lays out the “deep capture hypothesis” a bit more and begins loosely testing it by examining the role that it may have played in the “deregulatory” movement.

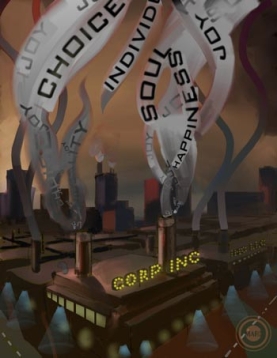

(Situationist artist Marc Scheff is providing the primary illustrations in this series.)

* * *

The Deep Capture Hypothesis

“The universal spirit of the laws, of every country is always to favor the strong against the weak and those who have against those who have not. This difficulty is inevitable, and it is without exception.”

~Jean Jacques Rousseau

“The twentieth century has been characterized by three developments of great political importance: the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power, and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.”

~Alex Carey

All of the key elements are in place. As with Galileo’s capture, today we have an extremely powerful institutional force with an immense stake in maintaining, and an ability to maintain, a false, though intuitive, worldview. Our basic hypothesis (and prediction) is that large commercial interests act (and will continue to act) to capture the situation–interior and exterior–in order to further entrench dispositionism. Moreover, they have done so largely undetected, and without much in the way of conscious awareness or collaboration. Hence, large corporate interests have, through disproportionate ability to control and manipulate our exterior and interior situations, deeply captured our world.

This is a hypothesis that finds support not just in the axiom of history repeating itself, although the lessons of history do indeed provide significant support. And it is a hypothesis that follows from more than just laboratory and field experiments of social psychology, although that literature alone should be sufficient to reverse our current presumptions. The deep capture hypothesis is also the logical extension of several basic economic insights, including those associated with capture theory and market theory– informed by a realistic understanding of the human animal (or situational character). The question remains, however, whether such a provocative, counterintuitive hypothesis finds much support in the various institutions that shape our exterior and interior situation.

Some Evidence of the Deep Capture Hypothesis

The deep capture hypothesis is too provocative to leave totally undefended, but covers too vast a set of institutions to adequately defend here. Much of the remainder of this [series of posts], therefore, will be devoted to providing a sample of observations that provide support for our framework. . . .

Here [in this series], we will attempt to show that history is, as usual, repeating itself — that we live in a world much like that of Galileo. The dispositionist worldview, which is so valuable to the most powerful institutions in our culture, is widely accepted in our population as common-sensical, even though that view is, according to the best available evidence, fundamentally lop-sided. Furthermore, those powerful institutions use their power to advance that view by actively promoting it themselves, by rewarding others who do so, and by seeking to penalize or delegitimate those who challenge it.

A. Some Shallow Evidence of Deep Capture

“Experience should teach us to be most on our guard to protect liberty when the government’s purposes are beneficial. Men born to freedom are naturally alert to repel invasion of their liberty by evil-minded rulers. The greater dangers to liberty lurk in insidious encroachment by men of zeal, well-meaning but without understanding.”

~Justice Louis Brandeis

First, we will consider the view of human beings adopted by the sort of administrative regulatory institutions that Stigler and his cohorts did focus on. Take, for example, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and [former] Chairman Michael Powell‘s conception of consumers and the corresponding presumptions about markets and regulation:

I am committed to building policy that is centered around market economics. At times, this foundation of my thinking is often questioned as being somehow anti-consumer. In a television interview, the question goes something like this: “Many consumer groups express grave concern that your laissez-faire approach will harm consumers. They say you are out of touch with consumers and living in an ivory tower. What say you?”

*

I am always a little puzzled by this question, for the premise of it has been so thoroughly discredited in this nation and in countries around the world that it should be beyond challenge. Market systems, far from being the bane of consumers, have unquestionably produced more consumer welfare than any other economic model devised by mankind. How is it that anyone can argue that the pro-market policies of the United States have not yielded enviable productivity in our economy, jobs for our citizens, a higher standard of living than nearly any other country in the world, and a tradition of innovation and invention that has brought new products, tools and services to our citizens?

*

A well-structured market policy is one that creates the conditions that empower consumers:

*

It lets consumers choose the products and services they want–which is their right as free citizens.

. . . .

It allows market forces to calibrate pricing to meet supply and demand. Consumers get the most cost-efficient prices and enjoy the benefits of business efficiencies.*

The result for consumers is better, more cutting edge products, at lower prices.

*

Contrary to the classic bugaboo that markets are just things that favor big business and big money, market policies have a winning record of delivering benefits to consumers that dwarfs the consumer record of government central economic planning. Thus, if you are truly committed to serving the public interest, bet on a winner and bet on market policy.

Thus, Powell views consumers as “free citizens,” who should therefore be allowed to “choose the products and services they want.” And, according to that conception of consumers, free choice should be enabled through “market systems,” which are the best mechanism ever “devised by mankind” for “delivering benefits to consumers,” “empower[ing] consumers,” and thereby producing “more consumer welfare.”

according to that conception of consumers, free choice should be enabled through “market systems,” which are the best mechanism ever “devised by mankind” for “delivering benefits to consumers,” “empower[ing] consumers,” and thereby producing “more consumer welfare.”

There are other noteworthy features of Powell’s remarks. For example, Powell frames his goals in terms of serving the “public interest,” but this is the same type of assertion that Stigler claimed could not be trusted. And certainly this “trust” issue has been raised. But Powell reassures critics by claiming that deregulation tends toward the “public interest:”

“In capital[ist] economies,” he writes, “the central premise is that the interests of producers (i.e., money-makers) and consumers need not diverge, but, in fact, can be synchronous.” That may be true, but it is equally true that a central premise behind regulation is that the interests of producers and consumers sometimes do diverge. As if to respond to that potential criticism, Powell takes a page from Stigler’s scholarly agenda, writing:

I am the first to admit that deregulation for its own sake is not responsible policy. What is good policy is to carefully examine rules to determine if they are actually achieving their stated purposes, or if, instead, they are, in fact, denying consumers value by impeding efficient market developments that these consumers would welcome. Regulations are not innocuous simply because they are promulgated in the name of consumers. No matter how worthy the purpose, rules that constrain markets can, in fact, deny or delay benefits to the consuming public.

Stigler himself could hardly have said it better. If you want to be sure that regulations (or deregulations) actually serve the public interest, then look at their effects. Thus, Powell’s vision of consumers, like that of virtually all of the country’s most prominent regulators, appears to be very close to the one that George Stigler complained regulators generally lacked.

But our hypothesis is that shallow capture is still a problem, in part because the advantages favoring large business interests in the competition for regulatory influence have not changed, even if the conceptions of consumers, markets, and regulations have. Thus, the same evidence that, to many scholars, might constitute proof of the absence of shallow capture, strikes us as evidence of deep capture–the faith in pro-market, anti-regulation dispositionism.

Finally, it is worth pointing out how Powell dismisses those who doubt that faith. He finds such apprehensions, not just “puzzl[ing],” but “so thoroughly discredited . . . that [his view] should be beyond challenge.” A major part of the discrediting comes from the fair competition that is presumed to have occurred in the global marketplace of political-economic systems, a competition that led to the “winning record” of markets and a “higher standard of living [in the United States] than nearly any other country in the world.” The not-very-hidden implication is that those who don’t embrace his views are favoring a turn toward “central economic planning,” perhaps even communism. Powell, in other words, dismisses what he calls “the classic bugaboo that markets . . . favor big business and big money” by raising the familiar specter of the totalitarian bogeyman.

A look at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), whose “efforts are directed toward stopping actions that threaten consumers’ opportunities to exercise informed choice,” is similarly revealing. The [former] FTC Chairman, Timothy Muris, seems to share Powell’s preference for  free markets, and for all the same reasons. In 1980, for instance, Muris wrote (with a co-author) that

free markets, and for all the same reasons. In 1980, for instance, Muris wrote (with a co-author) that

[t]he relatively unregulated marketplace has significant advantages in allocating resources and promoting consumer welfare. The market tends to minimize waste by permitting continuous individual balancing of economic costs and benefits by consumers and producers. In addition, greater productive efficiency and more innovation result from the reliance on market incentives. Competitive markets also reduce the need for central collection of information; their price signals allow producers and consumers to respond quickly to change. Finally, competitive markets tend to decentralize power and make decisions that are fair in the sense of being impersonal. For these reasons, reliance on the market should be the norm.

More recently, he has supplemented that pro-market view by emphasizing the need for certain types of regulatory interventions in markets. In 1991, for instance, he wrote that “[o]ne of the crucial roles for government, as we are seeing in Eastern Europe, is to define and allocate property rights.” And although he acknowledges the need for certain types of regulation when a market fails, he cautions that

it is important to talk about the concept of market failure with care because the issue is failure compared to what. In the real world, institutions are imperfect, both government institutions and market institutions. It makes no sense to compare an imperfect reality to a hypothetical perfection. A vast literature exists on government failure, as large as or larger than the literature on market failure.

With that caution, Muris appears to be emphasizing the work of, among others, George Stigler, for Muris goes out of his way to stress that

[g]overnment agencies are not run by philosopher kings who descend from Olympus to protect us. Instead, government agencies are, themselves, governed by rules that constrain what they can do, and they are run by individuals who are striving to advance or succeed, just as we all are. These constraints and incentives will influence how an agency acts in the public interest.

Muris also describes how FTC regulation of advertising has moved from protecting industry members from competition toward serving consumers by encouraging competition.

Again, the chairperson of a major federal regulatory institution seems to embrace the dispositionist case for markets–as does the Commission itself. Again, that regulator seems quite sensitive to the insights of shallow capture theory. And, again, we would conclude that, insofar as Chairman Muris fails to consider the role of exterior and interior situation, his views and, indeed, his position at the FTC, evince deep capture.

We could continue in this vein at some length, but for everyone’s sake, we will stop here.

* * *

The next post in this series digs a little deeper and provides some illustrative examples of how other “regulators,” from courts to hard-hitting news networks, reflect and contribute to deep capture.

Part I of this series explained that our “deep capture” story is analogous to the (shallow) capture story told by economists (such as Nobel laureate George Stigler) and public choice theorists for decades regarding the competition over prototypical regulatory institutions. Part II looked to history (specifically, Galileo’s recantation) for another analogy to the process that we claim is widespread today — the deep capture of how we understand ourselves. Part III picked up on both of those themes and explains that Stigler’s “capture” story has implications far broader and deeper than he or others realized. Part IV examined the relative power (measured as the ability to influence situation) of large commercial interests today, much like the power of the Catholic Church in Galileo’s day. Part V described other parallels between the Catholic Church and geocentrism, on one hand, and modern corporate interests and dispositionism, on the other.

All the posts in this series are drawn from the 2003 article , “The Situation” (co-authored with David Yosifon and downloadable here).

Rate this:

Related

This entry was posted on December 21, 2007 at 12:01 am and is filed under Deep Capture, Public Policy, Social Psychology. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

The Deep Capture Hypothesis of Individuals and Institutions « Cocking A Snook! said

[…] blogged here, authors Jon Hanson and David Yosifon describe a theory they call “Deep Capture”: The […]

Deep Capture - Part VIII « The Situationist said

[…] and geocentrism, on one hand, and modern corporate interests and dispositionism, on the other. Part VI laid out the “deep capture hypothesis” a bit more and began loosely testing it by […]

Deep Capture and The Situationist « Neuroanthropology said

[…] Hanson and David Yosifon lay out their theory most explicitly in Part VI. (For those of you interested in the most recent post, which contains links to the earlier posts, […]

Capture (Animated) « The Situationist said

[…] “Deep Capture – Part VI,” […]