Unlevel Playing Fields: From Baseball Diamonds to Emergency Rooms

Posted by The Situationist Staff on August 19, 2007

Previous Situationist posts have discussed the significance of implicit associations (a key feature of the human animal’s “interior situation”), including “Hoyas, Hos, & Gangstas,” “Race Attributions and Georgetown University Basketball,” “Black History is Now” and “Implicit Bias and Strawmen.” This post collects summaries of a number of recent studies suggesting how routinely implicit associations may bias decision making even among those individuals presumed to be least biased.

Previous Situationist posts have discussed the significance of implicit associations (a key feature of the human animal’s “interior situation”), including “Hoyas, Hos, & Gangstas,” “Race Attributions and Georgetown University Basketball,” “Black History is Now” and “Implicit Bias and Strawmen.” This post collects summaries of a number of recent studies suggesting how routinely implicit associations may bias decision making even among those individuals presumed to be least biased.

We begin with a press release and Katie Rooney’s Time article about a study indicating how baseball umpires may alter their strike zones based on the race or ethnicity of the pitcher. Then we include brief portions of Alan Schwarz’s (New York Times) summary of a study indicating similar bias on the basketball court. Finally, we turn to a fascinating new study co-authored by Situationist contributor Mahzarin Banaji. That study looks at how doctor’s judgments might be biased as summarized in the Boston Globe (by Stephen Smith from 07/20/07) and the Washington Post (by Shakar Vedantam 08/13/07) .

* * *

Daniel Hamermesh, the Edward Everett Hale Centennial Professor of Economics, finance professors at McGill and Auburn Universities and a University of Texas at Austin graduate student analyzed every pitch from three major league seasons between 2004 and 2006 to explore whether racial discrimination factors into umpires’ evaluation of players. . . .

Daniel Hamermesh, the Edward Everett Hale Centennial Professor of Economics, finance professors at McGill and Auburn Universities and a University of Texas at Austin graduate student analyzed every pitch from three major league seasons between 2004 and 2006 to explore whether racial discrimination factors into umpires’ evaluation of players. . . .

. . . . During a typical game, umpires call about 75 pitches for each team. Throughout the season, they call about 400,000 pitches.

The researchers found if a pitcher shares the home plate umpire’s race or ethnicity, more strikes are called and he improves his team’s chance of winning.

* * *

It doesn’t happen all the time — in about 1% of pitches thrown — but that’s still one pitch per game, and it could be the one that makes the difference. “One pitch called the other way affects things a lot,” says Hamermesh. “Baseball is a very closely played game.” What’s more, says Hamermesh, a slight umpire bias affects more than just the score; it also has an indirect effect on a team’s psyche. Baseball is a game of strategy. If a pitcher knows he’s more likely to get questionable pitches called as strikes, he’ll start picking off at the corners. But if he knows he’s at a disadvantage, he might feel forced to throw more directly over the plate, possibly giving up hits.

. . . . Controlling for all other outside factors, such as the pitcher’s tendency to throw strikes, the umpires’ tendency to call strikes and the batter’s ability to attract balls, researchers found evidence of same-race bias — and the data revealed that the bias benefits mostly white pitchers. Not surprising, since 71% of MLB pitchers and 87% of umpires are white.

The highest percentage of strikes were called when both the home-plate umpire and pitcher were white, and the lowest percentage were called between a white ump and a black pitcher. The study also found that minority umpires judged Asian pitchers more unfairly than they did white pitchers. It’s a significant disadvantage for Asian pitchers because the MLB doesn’t have any Asian umpires. Interestingly enough, Hamermesh’s research found that the race of the batter didn’t seem to matter — the correlation was only between the pitcher and the home-plate ump. Rich Levin, an MLB spokesman, refused to comment on the research findings.

Though his research confirms that bias exists, Hamermesh says it can be easily reduced or eliminated. When a game’s attendance is particularly high, when the call is made on a full count or when ballparks use QuesTec, an electronic system that evaluates the accuracy of umpires’ calls after the game, the biased behavior disappeared, according to the study. “The umpires hate those [QuesTec] systems,” Hamermesh says. “When you’re going to be watched and have to pay more attention, you don’t subconsciously favor people like yourself. . . .”

Hamermesh, who has studied discrimination at all levels, says that bias is instilled in infancy — much like enduring personality traits such as shyness or high self-esteem — as an essential part of human behavior. “We all have these subconscious preferences for our own group,” he says. . . .

But the takeaway message of his study is a hopeful one, says Hamermesh: discrimination can be corrected. “I expect that [MLB] will not be very happy about this, but the fact that with a little bit of effort this kind of behavior can be altered, that’s very gratifying. I wish with society as a whole we could reduce the impact of discrimination as easily as it could be done in baseball.”

* * *

An academic study of the National Basketball Association . . . suggests that a racial bias found in other parts of American society has existed on the basketball court as well.

An academic study of the National Basketball Association . . . suggests that a racial bias found in other parts of American society has existed on the basketball court as well.

A coming paper by a University of Pennsylvania professor and a Cornell University graduate student says that, during the 13 seasons from 1991 through 2004, white referees called fouls at a greater rate against black players than against white players.

Justin Wolfers, an assistant professor of business and public policy at the Wharton School, and Joseph Price, a Cornell graduate student in economics, found a corresponding bias in which black officials called fouls more frequently against white players, though that tendency was not as strong. They went on to claim that the different rates at which fouls are called “is large enough that the probability of a team winning is noticeably affected by the racial composition of the refereeing crew assigned to the game.”

. . .

“I would be more surprised if it didn’t exist,” Mr. [Ian] Ayres [at Yale Law School] said of an implicit association bias in the N.B.A. “There’s a growing consensus that a large proportion of racialized decisions is not driven by any conscious race discrimination, but that it is often just driven by unconscious, or subconscious, attitudes. When you force people to make snap decisions, they often can’t keep themselves from subconsciously treating blacks different than whites, men different from women.”

Mr. Berri [at Cal. State Bakerton] added: “It’s not about basketball — it’s about what happens in the world. This is just the nature of decision-making, and when you have an evaluation team that’s so different from those being evaluated. Given that your league is mostly African-American, maybe you should have more African-American referees — for the same reason that you don’t want mostly white police forces in primarily black neighborhoods.”

To investigate whether such bias has existed in sports, Mr. Wolfers and Mr. Price examined data from publicly available box scores. They accounted for factors like the players’ positions, playing time and All-Star status; each group’s time on the court (black players played 83 percent of minutes, while 68 percent of officials were white); calls at home games and on the road; and other relevant data.

But they said they continued to find the same phenomenon: that players who were similar in all ways except skin color drew foul calls at a rate difference of up to 4 ½ percent depending on the racial composition of an N.B.A. game’s three-person referee crew.

Mark Cuban, the owner of the Dallas Mavericks and a vocal critic of his league’s officiating, said in a telephone interview after reading the paper: “We’re all human. We all have our own prejudice. That’s the point of doing statistical analysis. It bears it out in this application, as in a thousand others.”

. . .

[The study found] “that black players receive around 0.12-0.20 more fouls per 48 minutes played (an increase of 2 ½-4 ½ percent) when the number of white referees officiating a game increases from zero to three.”

Mr. Wolfers and Mr. Price also report a statistically significant correlation with decreases in points, rebounds and assists, and a rise in turnovers, when players performed before primarily opposite-race officials.

“Player-performance appears to deteriorate at every margin when officiated by a larger fraction of opposite-race referees,” they write. The paper later notes no change in free-throw percentage. “We emphasize this result because this is the one on-court behavior that we expect to be unaffected by referee behavior.”

Mr. Wolfers and Mr. Price claim that these changes are enough to affect game outcomes. Their results suggested that for each additional black starter a team had, relative to its opponent, a team’s chance of winning would decline from a theoretical 50 percent to 49 percent and so on, a concept mirrored by the game evidence: the team with the greater share of playing time by black players during those 13 years won 48.6 percent of games — a difference of about two victories in an 82-game season.

. . . Both men cautioned that the racial discrimination they claim to have found should be interpreted in the context of bias found in other parts of American society.

“There’s bias on the basketball court,” Mr. Wolfers said, “but less than when you’re trying to hail a cab at midnight.”

* * *

Deeply imbedded attitudes about race influence the way doctors care for their African- American patients, according to a Harvard study that for the first time details how unconscious bias contributes to inferior care. Researchers have known for years that African-Americans in the midst of a heart attack are far less likely than white patients to receive potentially life-saving treatments such as clot-busting drugs, a dramatic illustration of America’s persistent healthcare disparities. But the reasons behind such stark gaps in care for heart disease, as well as cancer and other serious illnesses, have remained murky, with blame fixed on doctors, hospitals, and insurance plans.

Deeply imbedded attitudes about race influence the way doctors care for their African- American patients, according to a Harvard study that for the first time details how unconscious bias contributes to inferior care. Researchers have known for years that African-Americans in the midst of a heart attack are far less likely than white patients to receive potentially life-saving treatments such as clot-busting drugs, a dramatic illustration of America’s persistent healthcare disparities. But the reasons behind such stark gaps in care for heart disease, as well as cancer and other serious illnesses, have remained murky, with blame fixed on doctors, hospitals, and insurance plans.

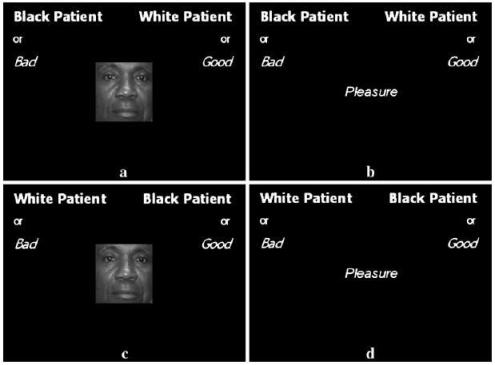

In the new study, trainee doctors in Boston and Atlanta took a 20-minute computer survey designed to detect overt and implicit prejudice. They were also presented with the hypothetical case of a 50-year-old man stricken with sharp chest pain; in some scenarios the man was white, while in others he was black.

“We found that as doctors’ unconscious biases against blacks increased, their likelihood of giving [clot-busting] treatment decreased,” said the lead author of the study, Dr. Alexander R. Green of Massachusetts General Hospital. “It’s not a matter of you being a racist. It’s really a matter of the way your brain processes information is influenced by things you’ve seen, things you’ve experienced, the way media has presented things.”

. . .

“Years of advanced education and egalitarian intentions are no protection against the effect of implicit attitudes,” said Dr. Thomas Inui, president of the Regenstrief Institute Inc. in Indianapolis, which studies vulnerable patient groups. “When do they surface? When we’re involved with high-pressure, high-stakes decision-making, when there’s a lot riding on our decisions but there isn’t a lot of time to make them, that’s when the implicit attitudes that are not scientific rise up and grab us.”

. . .”The great advantage of being human, of having the privilege of awareness, of being able to recognize the stuff that is hidden, is that we can beat the bias,” said [Situationist Contributor] Mahzarin R. Banaji, a Harvard psychologist who helped design a widely used bias test.

Dr. JudyAnn Bigby, Massachusetts secretary of health and human services and a specialist in healthcare disparities, said the study demonstrates the importance of monitoring how hospitals and large physician practices provide care to patients of different races.

But Inui and other specialists said that even conquering doctor bias will not be enough to eliminate healthcare disparities.

A succession of studies during the past decade has demonstrated graphically the scope of disparities and the complexity of the problem, which touches on issues from poverty to geography to genetics.

Black patients in the process of having a heart attack, for example, are only half as likely as whites to get clot-busting medication, and they are much less likely to undergo open-heart surgery. Similarly, African-American women receive breast-cancer screenings at a rate substantially lower than white women. Fewer black babies live to celebrate their first birthdays: In Massachusetts, the mortality rate for black infants is more than double the rate for white babies.

Healthcare disparities emerged as a national issue with the 2002 release of a landmark study titled “Unequal Treatment” that was commissioned by Congress and produced by the Institute of Medicine. In Boston, the city health department released a sweeping blueprint for addressing disparities two years ago, with Mayor Thomas M. Menino describing the issue as the most pressing health problem confronting the city.

“Most physicians are now willing to acknowledge that important disparities exist in the healthcare system,” said Dr. John Ayanian, a healthcare policy specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who was not involved with the new research. “There’s still a barrier, though, to many physicians acknowledging that disparities may exist in the care of their own patients.”

It was during a lecture three years ago by Banaji that Green came up with the idea of measuring the unconscious bias of physicians by using a test Banaji had helped develop .

Green and his colleagues decided to test residents at Massachusetts General, the Brigham, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, as well as at an Atlanta hospital. Residents were told that the study was evaluating the use of heart attack drugs in the emergency room, but not that it was also examining racial bias; 220 trainee doctors were counted in the results.

The residents were first given a narrative describing a male patient who shows up in the emergency room complaining of chest pains. Accompanying the narrative was a computer-generated image of the patient, either a black or white man shown in a hospital gown from the chest up, wearing a neutral facial expression.

The doctors were asked if, based on the information provided, they would diagnose the man as having a heart attack and, if so, whether they would prescribe clot-busting drugs called thrombolytics, commonly used in community hospitals to stabilize patients having heart attacks, and how likely they were to give those drugs.

Study participants were also asked questions designed to determine if they were overtly biased. Answers showed they were not.

Last, the residents took Banaji’s “implicit association test,” which is based on the concept that the more strongly test-takers associate a picture of a white or black patient with a particular concept, say cooperativeness, the faster they will make a match. White, Asian, and Hispanic doctors were faster to make matches between blacks and negative concepts and slower to make matches between blacks and positive ones. The small number of African- American physicians in the study were as likely to show bias against blacks as against whites.

The researchers then compared the implicit association test scores with the decisions about whether to provide the clot- busting medicine and found that doctors whose ratings of African-Americans were most negative were also the least likely to prescribe the drug to blacks.

. . .

“At the end of the day, even among very well-intentioned people, implicit biases can be both prevalent and in some situations can impact clinical decisions,” said Dr. Amal Trivedi, a healthcare disparities specialist at Brown Medical School who was not involved in the study. “What this study can do is raise awareness of that finding.”

* * *

Green said numerous other studies are underway to evaluate the utility of psychological tests for bias to explain disparities in medical domains. “We have reason to suspect you can measure unconscious bias among physicians and show it has an impact on treatment decisions,” he said.

Mahzarin Banaji . . . said the racial bias unearthed by the study is at odds with conventional views of bigotry — and perhaps more insidious. Rather than harboring deliberate ill will, she said, the physicians had apparently internalized racial stereotypes, and these attitudes subtly influenced their medical judgment without their even realizing it.

The study of physicians had one hopeful note, Banaji said: Doctors at least were willing to open their subconscious minds for inspection, which is something that many other professionals — judges, police officers and NBA referees — rarely are willing to do.

* * *

For an NPR Talk of the Nation audio discussion of the NBA study and reactions to it, click here. For an NPR Tell Me More audio discussion of the heart-attack study, click here.

Rate this:

Related

This entry was posted on August 19, 2007 at 12:01 am and is filed under Choice Myth, Implicit Associations, Situationist Sports, Social Psychology. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

John J Perricone said

Guys, Hammermesh should be ashamed of himself. 1 pitch called with racial bias could change a game outcome? I can hardly count the ways in which that statement is absurd. Of course, for the person behind the study to conclude that a 1% difference is impactful should surprise no one, but for so many articles to be written about it, and for so many writers to leave him alone from challenge is tremendously frustrating and disappointing.

Please take the time to think about what 1 pitch out of 75 might really do, and I believe you will see that his study was a waste of time.

I’m Objective, You’re Biased « The Situationist said

[…] on your perspective, one part or another of the media is obviously biased. In the sports world, referees and umpires often seem less than fully neutral. And on the bench, even robed judges sometimes appear to have […]

Thoughts on NBA Officials, MLB Umpires, and Implicit Attitudes & Joba Chamberlain’s Pitching and Suspension - Gorkemgozleme Sports | World's Sport News said

[…] Implicit attitudes are likely to be the subject of many other sports-related studies, and as Francesa Di Meglio of Business Week reports this week, there is a new study examining baseball umpires and implicit attitudes. In her piece “Racism Behind the Plate?” Di Meglio discusses the research of University of Texas economics professor Daniel Hamermesh and his co-authors. They find that due to implicit attitudes, Major League Baseball umpires make calls that favor pitchers who share their ethnicity and race. The authors examined every pitch from three Major League Baseball seasons between 2004 and 2006 to determine if racial discrimination played any part in umpire calls, and discovered that when the pitcher shares the home plate umpire’s race or ethnicity, more strikes are called. According to the authors, given that there are more white umpires (87% are white) and white pitchers (71% are white), minority pitchers are more likely to show less favorable results and ultimately be undervalued. Their paper can be downloaded here and a related Situationist post can be read here. […]

Thoughts on Michael Vick, Tim Donaghy, and Baseball Umpires’ Implicit Attitudes - Gorkemgozleme Sports | World's Sport News said

[…] on The Situationist, we examine a new study indicating how baseball umpires may alter their strike zones based on the race or ethnicity of the […]