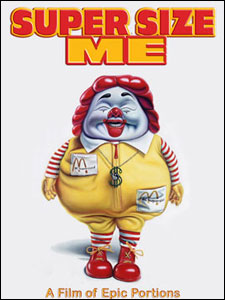

Situational Obesity, or, Friends Don’t Let Friends Eat and Veg

Posted by The Situationist Staff on August 2, 2007

No one would deny that your friends have a profound effect on your personality and what you find to be socially acceptable. A group of friends develops inside jokes, shared history, and gestures that instantly convey complex meanings. They also influence each member’s views of how people should act in groups and what is acceptable behavior. Sense of humor, language deemed acceptable, and actions that are allowed and frowned upon all develop within a group.

No one would deny that your friends have a profound effect on your personality and what you find to be socially acceptable. A group of friends develops inside jokes, shared history, and gestures that instantly convey complex meanings. They also influence each member’s views of how people should act in groups and what is acceptable behavior. Sense of humor, language deemed acceptable, and actions that are allowed and frowned upon all develop within a group.

It should not surprise us to learn that our social groups also influence our appearance — from how we dress, to whether we like or are turned off by tattoos and piercings. A recent study shows that this group influence may go further than most of us probably assume and may even influence obesity rates. A great deal has already been written on the situational sources of obesity. But this study sheds light on how body type and fitness may be connected to one situational feature that has been largely missed in previous work: friendships, social connections and their associated implicit (perhaps sometimes explicit) group norms . Dr. Nicholas Christakis of Harvard Medical School and James Fowler, a political scientist at the University of California San Diego, followed the weight levels of more than 12,000 Framingham, MA residents over a 30 year period and found some shocking correlations. Gina Kolata of the International Herald Tribune reports.

* * *

Obesity spreads to friends, study concludes

by Gina Kolata

Obesity can spread from person to person, much like a virus, according to researchers. When one person gains weight, close friends tend to gain weight too.

Their study, published Thursday in the New England Journal of Medicine, involved a detailed analysis of a large social network of 12,067 people who had been closely followed for 32 years, from 1971 until 2003. The investigators knew who was friends with whom, as well as who was a spouse or sibling or neighbor, and they knew how much each person weighed at various times over three decades.

That let them watch what happened over the years as people became obese. Did their friends also become obese? Did family members? Or neighbors?

The answer, the researchers report, was that people were most likely to become obese when a friend became obese. That increased one’s chances of becoming obese by 57 percent.

There was no effect when a neighbor gained or lost weight, however, and family members had less of an influence than friends. It did not even matter if the friend was hundreds of miles away – the influence remained. And the greatest influence of all was between mutual close friends. There, if one became obese, the other had a 171 percent increased chance of becoming obese too.

The same effect seemed to occur for weight loss, the investigators say, but since most people were gaining, not losing, over the 32 years, the result was an obesity epidemic.

Dr. Nicholas Christakis, a physician and professor of medical sociology at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator in the new study, says one explanation is that friends affect each others’ perception of fatness. When a close friend becomes obese, obesity may not look so bad.

“You change your idea of what is an acceptable body type by looking at the people around you,” Christakis said.

The investigators say their findings can help explain why Americans became fatter in recent years: Persons who became obese were likely to drag some friends with them.

Their analysis was unique, Christakis said, because it moved beyond a simple analysis of one person and his or her social contacts, and instead examined an entire social network at once, looking at how a friend’s friends’ friends, or a spouse’s siblings’ friends, could have an influence on a person’s weight. The effects, Christakis said, “highlight the importance of a spreading process, a kind of social contagion, that spreads through the network.”

Of course, the investigators say, social networks are not the only factors that affect body weight. There is a strong genetic component at work too.

Science has shown that individuals have genetically determined ranges of weights, spanning perhaps 30 or so pounds, or 13.5 kilograms, for each person. But that leaves a large role for the environment in determining whether a person’s weight is near the top of his or her range or near the bottom. As people have gotten fatter, it appears that many are edging toward the top of their ranges. The question has been why.

If the new research is correct, it might mean that something in the environment seeded what many call an obesity epidemic, making a few people gain weight. Then social networks let the obesity spread rapidly.

It also might mean that the way to avoid becoming fat is to avoid having fat friends.

That is not the message they meant to convey, say the study investigators, Christakis and his colleague James Fowler, an associate professor of political science at the University of California in San Diego. You don’t want to lose a friend who becomes obese, Christakis said. Friends are good for your overall health, he explains.

That is not the message they meant to convey, say the study investigators, Christakis and his colleague James Fowler, an associate professor of political science at the University of California in San Diego. You don’t want to lose a friend who becomes obese, Christakis said. Friends are good for your overall health, he explains.

So why not make friends with a thin person, he suggests, and let the thin person’s behavior influence you and your obese friend?

That answer does not satisfy obesity researchers like Kelly Brownell, director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at Yale University.

“I think there’s a great risk here in blaming obese people even more for things that are caused by a terrible environment,” Brownell said.

On average, the investigators said, their rough calculations show that a person who became obese gained 17 pounds, and the newly obese person’s friend gained 5 pounds. But some gained less or did not gain at all, while others gained much more.

Those extra pounds were added onto the natural increases in weight that occur when people get older. What usually happened was that peoples’ weights got high enough to push them over the boundary, a body mass index of 30, that divides overweight and obese. (For example, a man 6 feet, or 1.8 meters, tall who went from 220 pounds to 225 would go from being overweight to obese.)

Their research has taken obesity specialists and social scientists aback. But many say the finding is path-breaking and can shed new light on how and why people have gotten so fat so fast.

“It is an extraordinarily subtle and sophisticated way of getting a handle on aspects of the environment that are not normally considered,” said Dr. Rudolph Leibel, an obesity researcher at Columbia University in New York.

Dr. Richard Suzman, who directs the office of behavioral and social research programs at the U.S. National Institute on Aging, called it “one of the most exciting studies to come out of medical sociology in decades.” The National Institute on Aging funded the study.

But Dr. Stephen O’Rahilly, an obesity researcher at the University of Cambridge in England, says the very uniqueness of the Framingham data is going to make it hard to try to replicate the new findings. No other study he knows of has the same sort of long term and detailed data on social interactions.

“When you come upon things that inherently look a bit implausible, you raise the bar for standards of proof,” O’Rahilly said. “Good science is all about replication, but it is hard to see how science will ever replicate this.”

* * *

For an NPR, Morning Edition transcript and audio report about the study click here. For a collection of previous, related Situationist posts discussing the role of situation in obesity, click here. To link to an article by Situationist contributors, Adam Benforado, Jon Hanson, and David Yosifon on the situational sources of the obesity epidemic, click here.

Rob said

Nice post.

We’ve a real problem with obesity.

In fact I recently blogged about this exact thing here: http://tinyurl.com/38zvkm

In short: In May of 2002, the World Health Organization announced a rise in obesity, diabetes and heart disease. Remarkably, this occurred not only in affluent developed nations – but also among developing nations in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean, where malnutrition was once the major dietary issue.

Obesity in the developing world can be seen as a result of a series of changes in diet, physical activity, health and nutrition, collectively known as the ‘nutrition transition.’ As poor countries become more prosperous, they acquire some of the benefits along with some of the problems of industrialized nations. These include obesity.

Since urban areas are much further along in the transition than rural ones, they experience higher rates of obesity. Cities offer a greater range of food choices, generally at lower prices. Urban work often demands less physical exertion than rural work. And as more and more women work away from home, they may be too busy to shop for, prepare and cook healthy meals at home. The fact that more people are moving to the city compounds the problem. In 1900, just 10 percent of the world population inhabited cities. Today, that figure is nearly 50 percent.

Read more here: http://tinyurl.com/2scnhk

Frank said

You’re doing a great job covering this…I’ve blogged responses here:

http://www.concurringopinions.com/archives/2007/03/recognizing_an.html

and

http://www.concurringopinions.com/archives/2007/07/the_genius_of_m.html

The “situationist” frame is critical, because otherwise people who want to cut funding for health care are likely to say the obese are violating the “duty to be healthy:”

http://www.concurringopinions.com/archives/2007/05/three_critiques.html

Social Networks « The Situationist said

[…] and Fowler, see “Common Cause: Combating the Epidemics of Obesity and Evil,” and “Situational Obesity, or, Friends Don’t Let Friends Eat and Veg.” For Situationist posts discussing the situational sources of obesity, click […]

oh yes said

i wanked

An Inspiring Story or Another Distorted Messages on Obesity? « The Situationist said

[…] Situational Obesity […]

McDonald’s Favorite Man: Don Gorske « The Situationist said

[…] Situational Obesity […]